A point from a previous blog post (sometimes, inspiration does not strike rather than tap you on the shoulder) has inspired this missive: you’ve got to ensure contestants have a lovely day, whether they’re on Take Your Pick for a few seconds or on Going for Gold for (seemingly) weeks.

Below is a by all means non-exhaustive list which gives an outline as to how much airtime contestants on certain game shows will get and the most disparity between them. (In other words, if, God forbid, you’re looking to take part in a quiz show in an attempt to become famous, the ones towards the end are what you should go for, even if they’ve not been commissioned in years.)

Take Your Pick

Minimum time: 5 seconds. Maximum time: 30 minutes

*Contestant walks on to cheesy music; maybe waves at family in the crowd; palpable excitement*

Hostess: This is Maureen from Darlington.

Host: Ah, hello Maureen, nice to meet you, are you well?

Contestant: Yes…

*Gong sounds, contestant tries not to swear, cheesy music returns, next contestant ferried in*

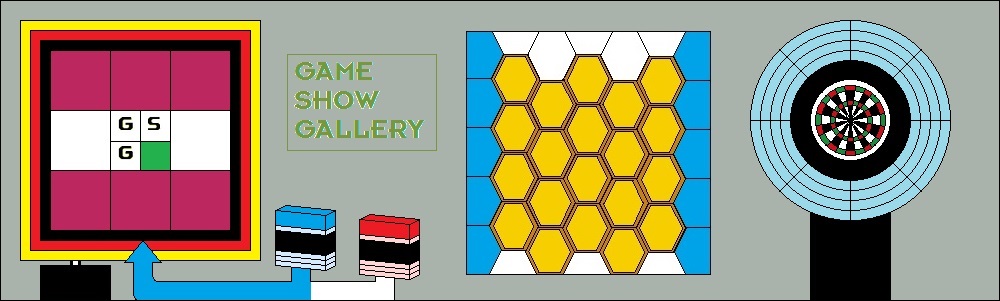

And off they went: on pretty much every edition of Take Your Pick, a contestant would be eliminated thus on the Yes/No Game (above) achieving only a few seconds of fame (and countless Christmases of infamy assuming family and friends had remembered to record it).

The rest of the show, which was pretty unmemorable in comparison, consisted of opening boxes, avoiding booby prizes, and hopefully winning a holiday.

Fluke

Minimum time: 2 minutes. Maximum time: theoretically one series, but in reality, two episodes

Ah, Fluke. What a wonderful show. Tim Vine was to appear later in 1997 as the first face of Channel 5 and the host of Whittle, but for some, his finest hour was earlier that year in this Channel 4 show.

The clue was in the name. Contestants had to answer impenetrable questions and, basically, be jammy as anything in order to win. The show also threw caution to the wind for traditional formats; rounds would take place whereby if a contestant lost despite being potentially hundreds of points in front, they were out.

Fluke finds a place just after Take Your Pick because of its very first round, where the Bit of a Wasted Journey Pointer would land on one unfortunate contestant and that would be the end of their day barely two minutes into proceedings (well, two minutes into their proceedings; the show would usually start with a two minute gag intro). Winning contestants were invited back to have another go, so theoretically the luckiest person in the world could go through a whole series. Remarkably, two contestants came back a second time and won again.

Fifteen to One

Minimum time: 5 minutes. Maximum time: several years (or approx. 20 programmes)

As Marcus Berkmann once mused in his excellent book Brain Men, why did so many people volunteer to go on Fifteen to One? Of course, there were jokes that it was a refuge for the unemployed and retired – the record Game Show Gallery has seen in one episode is nine out of 15 contestants – but again, the clue was in the name. The chances of winning were minimal, while the chances of making a complete berk of yourself on national TV were relatively odds-on.

Even if you thought you had a good solid general knowledge, you could get two stinkers in the first round, that was that, and you sat in the dark for the remaining 20 minutes knowing your friends had video recorders at the ready.

Conversely, the best performing player in Fifteen to One’s history, in terms of episodes and years spent on the show, was Anthony Martin. He started in 1988’s second series, and was only finally knocked out in series 13, in 1994.

Blockbusters

Minimum time: 10 minutes. Maximum time: several shows

Now we’re getting into different types of well-established formats. This, for those well-versed with this blog, is the ‘fall over’ format; you just keep playing until time runs out, and if a resolution has not been reached, you just carry on again in the next episode.

Normally a practice for five-shows-a-week/five-episodes-a-day programmes – Lucky Ladders was another, and they indulged in the practice of showing all the contestants on Contestants’ Row which meant you knew they were recording episodes in bulk – it was also used by Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, although the fastest finger first contestants were replaced each show, those who had failed to make the hot seat cursing their bad luck with their BFH.

As a result, contestants who did well had the chance to appear on several shows back to back. In WWTBAM, this usually meant a maximum of two shows, while Blockbusters and Lucky Ladders could carry on for the better part of a week.

The Great British Bake Off

Minimum time: 60 minutes. Maximum time: 14 weeks

Yes, it’s an example of the ‘balloon debate mechanism’ theory, so essentially this is just one of many such shows that could have been chosen. This blog has already covered the format, and how some influential figures in TV think it’s on its last legs, but as a reminder, you have x contestants at the beginning of a show, then lose one every week until you get a winner. Apprentice, X Factor, Big Brother…you get the idea.

In terms of what you see on screen, it’s almost antithetical in terms of distance and time. Those who get booted off on show one will usually get a lot of screen time in that one show – usually showing how rubbish they are – while the quieter ‘blimey, I didn’t even know they were in it’ types progress further.

Despite this, there can be exceptions. Many I’m A Celebrity… viewers from the most recent series – which had Gogglebox’s Scarlett Moffat declared the winner – were incensed at how much screen time she got and whether that may have subconsciously influenced the voting from the producers’ side. Mind you, the Digital Spy forum seems to have that conversation every year anyway.

Going for Gold

Daphne Fowler (nee Hudson, as was) collects her prize for winning the first series of Going for Gold

Minimum time: 1 week. Maximum time: 24 weeks (or approx. several programmes)

“What am I? I am a late 80s and 90s kitschy pan-European game show which seemed to go on forever and was hosted by an Irishman with an accent as thick as clotted cream…”

Correct, Going for Gold – and you answered that in the four point zone so now your opponent is playing catch up. With Brexit looming on the horizon, could a show which brought Europe together like nothing else since Eurovision – and usually confirmed our continental cousins were light years smarter than ourselves – be the boon that we all need?

Probably not, considering it was brought back in 2008 and felt outdated then. But the original Going for Gold meant you were guaranteed a solid amount of time on the show whether you did well or badly, but not necessarily a huge amount of screen time. If you fell at the first round, where your opponent only needed to get two questions correct to advance, your show ended after about five minutes. Multiply that by four and that was the lowest amount of time you got. If you won in the first week and then went on to win the whole series, for instance, your first and last appearances would be somewhere in the region of six months apart.